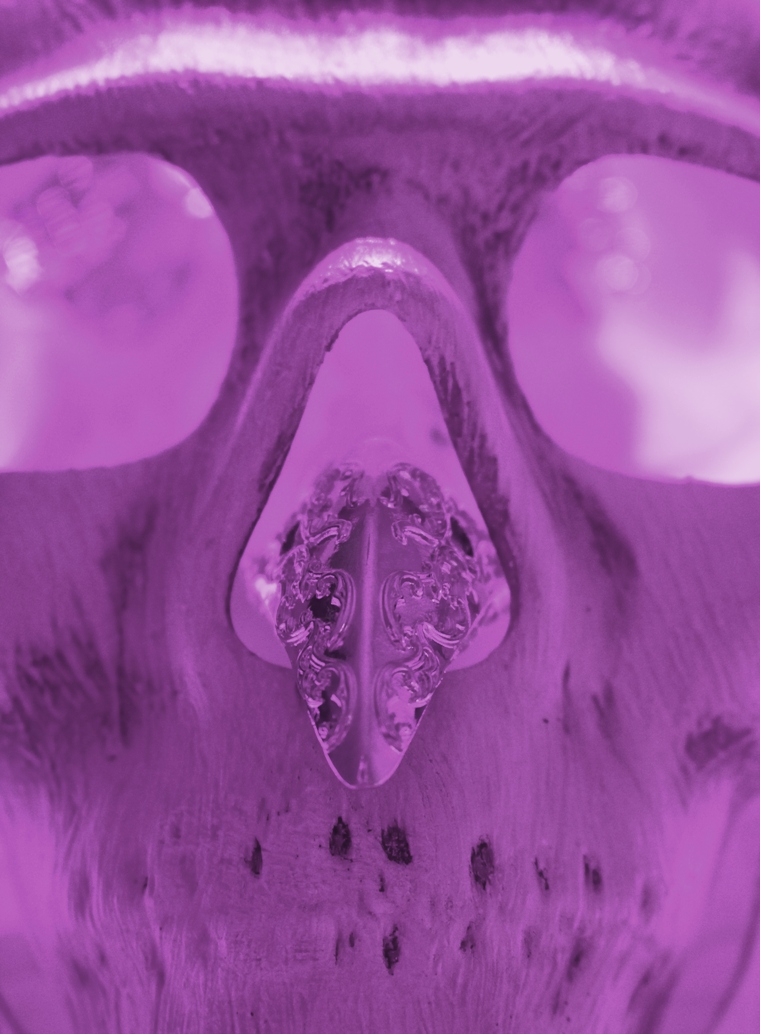

“We all wear masks, and the time comes when we cannot remove them without removing some of our own skin.†– Andre Berthiaume

We make our way along Boston Common and then the Public Garden, where Ilagan was married in 2010. He ushers us along one edge, as is his usual wont when passing by, pointing out where they stood during the ceremony. It’s a comfort to pass through, even as evening has arrived, and the leaves have started falling in earnest. He recalls their wedding lunch at the Four Seasons across the street. Even at a distance, Andy is never that far away. In the same way that he informs much of Alan’s blog (as do many of us friends and family if I may be so bold to say), he is present even in absentia.

The scent of early fall is in the air, and walking beside him and thinking of this online cast of misfits and familiar characters makes me feel slightly less alone in the world, even as it grows ever colder and dimmer. The hour, already christened the saddest of the day, adds to the melancholy dampness that suddenly stands between us and the long walk back to the condo. Alan senses something too, and just as we exit the Garden he suggests one more stop for tea at the Taj.

A sumptuous couch is open in one corner and he quickly makes it his own, dropping his shopping bags and relaxing onto its arm like he owned it. He requests a list of teas from the slightly snooty server, dismissing my annoyance at the attitude of said server, and settles on a peppermint herbal selection. “No caffeine for me, ever,†he pronounces. “I need to sleep tonight.†Here, in another place where people make their temporary homes away from home, I wonder at his propensity for hanging out in hotels. It’s been a habit of his from the time I’ve known him, and all these years later he still thrills at the notion of transitory strangers. He doesn’t want to examine the notion much. “Maybe I just like other people to make the bed?†he ponders before swerving us back to his new project. If I wanted to get deeper, peppermint tea was not the way. Yet he is passionate about the new work, and as he delves into it he gets as animated as when talking of friends.

“The whole idea of certain people being perverted has always been fascinating to me,†he says. “Is it society that that has perverted us or is it we who have perverted society? Is a gay person more perverted than a leader who believes certain minorities are less than human? Why is it more perverted for me to love my husband than for a stranger to hate us because we’re gay? That notion of where true perversion lies formed the impetus for this project.†He is off on a trip now, galloping quickly as his words tumble out between sips of tea.

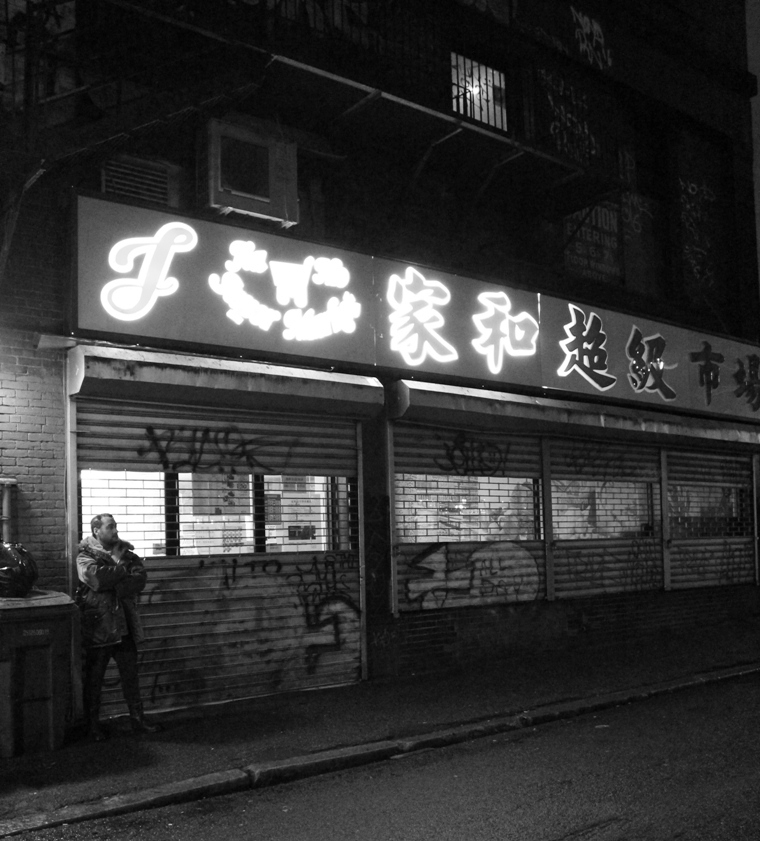

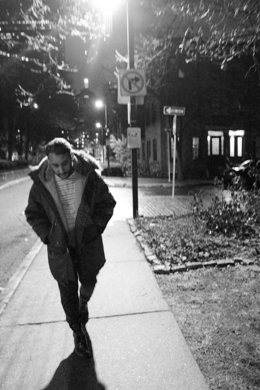

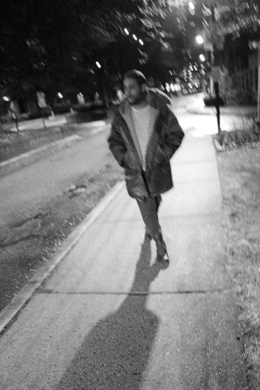

“I also found myself returning to the artistic aspect of photography and using the camera as a means of communicating an idea or a thought. Just images and whatever narrative the viewer brings into it. I wanted the photographs to indicate something missing. Empty space. I wanted to capture that feeling of emptiness, but also something haunting. Faded spirits. Foreboding. Ominous. Dread. A haunted aspect as if something or someone was missing. Photos that beg the questions: what happened here? Did someone disappear? What is missing? Is someone waiting? I wanted there to be tension and a taut sense of mystery. A sense of doom.â€

There is a palatable tension to much of the project. Photos that initially read as mundane – an empty doorway, a deserted run-down factory, a dirty patch of snow – gradually turn into something more upon closer and longer examination. The cover is a ghostly vision of Alan, jarringly out of focus and barely recognizable as human, which looks like he could be dancing or being hung. That about sums up the different and disparate levels of meaning and image that run through the work. It is surprisingly complex, and eons beyond anything he’s done before.

He is somewhat critical of past projects, saying, “Most of my photos have been very posed and choreographed and set up just so. Very staged, very still, and there’s not a lot of movement in it. I wanted to do something different and new to convey movement and restlessness. So much of my previous work is stationary. Dramatic, yes, and over the top with costumes and stuff, but not in movement or action. Everything is perfectly posed, backgrounds meticulously created, framed and designed. It is deliberately formal. This project is raw, casual, entirely of-the-moment. It is urgent and transient, indicative of change and transformation. It also goes against so much of what I see today – on Instagram for example.â€

Alan has a growing Instagram following, in addition to his formidable FaceBook presence (when he’s not being banned), a sizable Twitter account (verified, no less) and even an oft-neglected YouTube Channel (“Do subscribe!” he begs). Unlike some people, however, particularly those with much larger followings, he uses most of his social media outlets as light entertainment. Granted, his Twitter account veers hard into political retweets, and he is often calling out the current President for stupidity, cruelty, and simple nonsense, but for the most part Ilagan uses his social media accounts to drive traffic to his blog. “The rest is just fluff, honestly. People take those things way too seriously. For a long time I did too, but as much as I make use of them, they actually have little impact on real life.â€

He will expound upon the virtual online world that is being created, and he owns up to being a part of it, but is hyper-wary of it. “I’m the first to post about a new coat or pair of shoes I got, or a trip to see a Broadway show, and cumulatively the world gets a very skewed notion of how I live my life. I don’t document getting up at 5:30 every morning to get to work, or sitting at my office desk, or getting home and typing a week of blog posts into my laptop. Yet those are what constitute the bulk of my daily life. On Instagram though? I’m a fucking star who lives a glamorous life where the only thing I need to do all month is try out the latest Tom Ford Private Blend.â€

If ‘PVRTD’ is a social commentary on today’s political world, it is also as much a statement on Ilagan’s own artistic evolution, and how his creative work fits into the current pop culture environment. The advent of social media has resulted in a platform for everyone to act like a star, and all the filters and apps and fancy digital tricks have given even the dullest person an opportunity to shine. That comes with benefits and drawbacks. The playing field may feel more even, but it’s also more vast, and in such a climate where the masses can theoretically put forth their own content in the same exact way that Kim Kardashian or the President does, something has to set people apart from one another. As Alan and I sit near each other, engaging in a conversation, following the threads of where thoughts and listening lead us, I’m struck by how suddenly old-fashioned such a scene has become. In this ancient hotel of this most ancient city, we are relating as humans have related since we first learned to communicate. No one under the age of 30 would dare be caught idly sipping tea and simply talking without a cel phone within safe reach. It all feels slightly sad, and I wonder if that makes me old.

Alan mentions going into “old curmudgeon mode†and indulges in a bit of lamenting to go along with my train of thought. As much as the landscape of ‘PVRTD’ is a new challenge for him, the process of its creation marks a return to where he actually began.

“Today everything is in sharp focus, brilliant color, and has this impossible-to-ignore sheen,†he explains. “With our filters and photoshop we can make perfect images, even from rather rough raw material. I didn’t want to do that for this project. I’ve never been a big photoshop fan. If you can’t take a decent photo without excessive filters and effects, then you need to work on that first. I wanted these shots to be unfiltered and unfettered by those bounds of perfection. I wanted it to be a throwback to film, when a hand or arm or foot was inadvertently part of the finished product, when you caught what you could catch in the blink of an eye, and didn’t take a series of bursts from which you could get the best shot. I wanted the immediacy of that, yet also the time-freezing and time-catching that was a hallmark of film.†To that effect, ‘PVRTD’ is strikingly effective, and plants Ilagan squarely in the realm before the arrival of digital cameras.

“It feels like moments and photos are more fluid today. There are so many ways of capturing pictures, it’s no longer so strict and unforgiving. When you used film, you had the 24 or 36 prints that were available on a roll, and that was it. You had to reload, do it all over again, and send it away to get processed if you didn’t develop them yourself. You didn’t see how things were progressing, whether you needed more or less light, until days or weeks later. Most of the time you worked with what you got, even if it was less than perfect, and tried to make it better the next time.

Conversely, today’s technology allows for instant correction – not only in the editing process but in the act of taking the photos themselves. You can see what it will look like instantly on the screen and readjust instantly. I didn’t want to do that. I wanted it to be like one roll of film, where you had to use what you got. It gave the thing a feeling of daring, of risk, of possible failure. But it gives an absolute rendering of a moment that is less staged and artificial. What happened was what got captured. There were no repeats, no retakes, no additional opportunities to make things better or prettier.â€

If it sounds like he may be pining for a by-gone era, don’t be fooled: his website exists precisely because of the advance of the internet. It’s not lost upon him, yet his Thoreau-like aversion to too much technology has kept him mostly on the creative side of things (even if he can tell you what “HTML†code stands for). As we finish our tea, I look around the beautiful room, at the Public Garden across the street, and I yearn for a little bit of the past. A little bit of our youth. A little bit of what the world was once like. At the end of this day, it feels like it’s all gone.

We part in the lobby of the Taj, near the bottom of a circular staircase and beside a banquette of seasonal flowers. Alan always walks through this space just to see the floral arrangements; he still recalls the bountiful bouquets of peonies and cherry blossoms that marked his wedding stay all those many years ago. It is a fitting end to our Boston interviews. He will go back to the condo and sleep on the couch, listening to the sounds of the Braddock Park fountain before it is drained and put to bed for the winter. We’ll rendezvous at his home in upstate New York in a few days for one last interview session. He sweeps through the revolving door and disappears into the night.

{To Be Continued… Also see Part 1, Part 2 & Part 3}