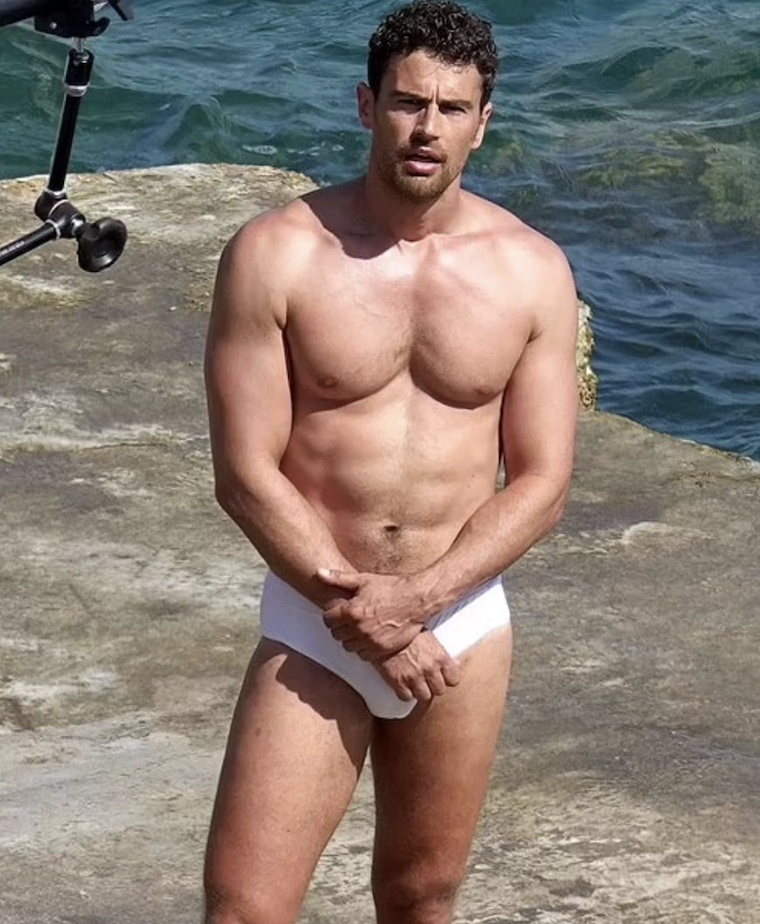

The news these days… am I right? Forget that nonsense and indulge in this little collection of shirtless male celebrities for your Sunday morning perusal, and clock on the accompanying links to see more of each. We begin with Theo James, who provided a few rousing out-takes from an upcoming Dolce & Gabbana commercial featuring their iconic white Speedo (and originally filled out by David Gandy).

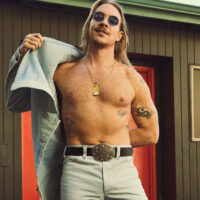

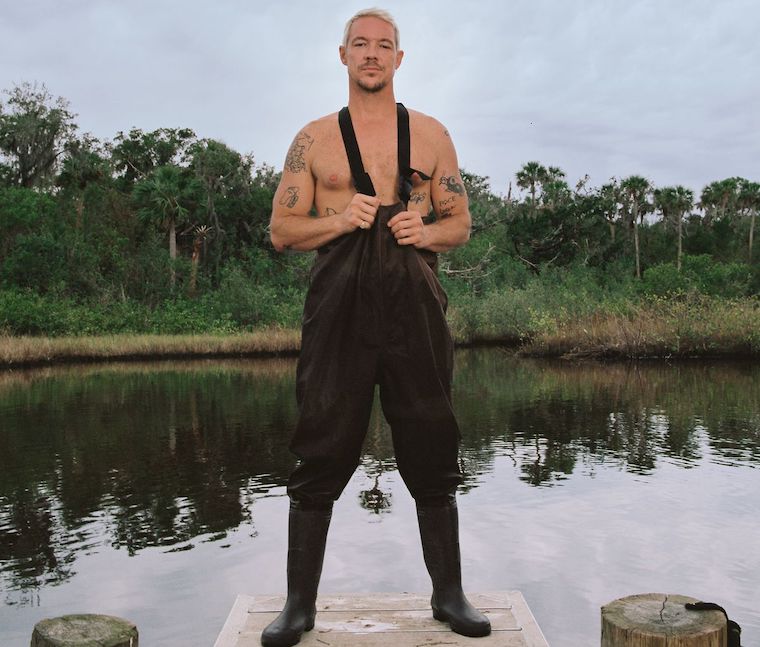

Next up is Bad Bunny, who needs only a pair of heart-shaped sunglasses to make an impressive impression. (See his crowning as Dazzler of the Day for further proof.)

A pair of Shawn Mendes poses in his Calvins because two is better than one in such matters. There are far too many posts of Mr. Mendes on this blog to link up here – but for a basic beginner’s kit, try this one or this one.

Michael B. Jordan rises from the pool, a proper heat-drenched summer moment if ever there was one. Mr. Jordan has been here before, opening this other shirtless male celebrity post, as well as closing out this one.

Lastly, Manu Rios keeps the heat going with a simple shirtless pose to close these Sunday morning proceedings. See some of his amazing fashion sense on display in his Dazzler of the Day crowning.