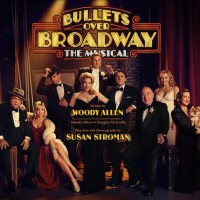

With its epochal questions of the artist versus the man, ‘Bullets Over Broadway’ is a good musical that wants to be great, but falls just slightly short of that unreachable goal. Like its flawed hero David Shayne, it performs admirably enough, but misses that final pull on the heartstrings that would make this more than what it is – which is, thanks to an ensemble of sheer perfection – already a pretty good show. (When Karen Ziemba is relegated to a rather minor supporting role, you know the talent pool is deep.) Luckily for this premiere staged version, that talented cadre of a cast is what lifts it into something better than its lighter-touch would have anyone presume.

Before you consider purchasing tickets, the bad news upfront is that I saw the show on its closing day. There’s something special about the closing performance of a relatively new musical, and this one proved exceptionally powerful, with the cast and crew rising to the occasion to produce a series of show-off-numbers and comedic gold. Making his leading man stage debut, Zach Braff as David Shayne takes the helm and carries the show on his more than capable shoulders. Broadway veteran Marin Mazzie (of ‘Passion’ and ‘Ragtime’ fame) fittingly portrays Broadway diva Helen Sinclair, in a role originated onscreen by the great Dianne Wiest. Comparisons are inevitable, but Ms. Mazzie’s golden voice supersedes any messy holes in the plot – though this reveals the fatal weakness of the production: these performers are far better than the material.

Whereas the movie was more of a comedic farce, the stage version leans a bit too heavily on the artist/man hang-up at one moment, before falling into broad humor the next. It can’t quite make up its mind whether to wallow in the pathos of the moral questions at hand or gloss over it all with superb stage presence. Some shows can have it both ways, but not this one.

Talent will always rise above, however, and this show had it in spades. There’s the aforementioned Braff and Mazzie, who perform the most moving highlight of the show – ‘There’s a Broken Heart for Every Light on Broadway’ – and by the end of it, as waves of applause echoed through the St. James Theatre, you could see Mr. Braff wipe a few tears from his eyes, perhaps realizing the bittersweet ending of a dream. He need not cry about it – his performance was pitch-perfect, and his singing voice was a revelation. It’s no mean feat to go head-to-head with a Broadway pro like Mr. Mazzie, but Mr. Braff more than held his own.

Hélene Yorke snatched the bulk of the laughs with her dithering portrayal of the worst actress in the world, Olive Neal. As her mafia-man sugar daddy, Vincent Pastore brings some slithering Sopranos charm to his mobster role, while Brooks Ashmanskas brings belly laughs (literally) as the ever-expanding Warner Purcell. With charisma and charm, and equal parts generosity and menace, reaches into the rafters with his spot-on portrayal of secretly-talented hit man Cheech, whose creative relationship with Braff’s Shayne is more interesting than any of the other predictable romances. Yet not enough is made of this, and not enough is done to make this anything more than the movie version come to imitated life.

Still, there are glimmers of what could have been. In many ways, this is a throwback to a more innocent Broadway, when song and dance and triple-threat performers wowed audiences with their sheer precision and bombast. That was most evident in the raucous take on ‘Taint Nobody’s Business If I Do.’ For those of us who started off almost cringing at the idea of a dancing chorus line of mobsters, the troop quickly won most over with their exuberance, their talent, and the sheer force of their will to entertain.

As good as the actors give, the show itself fails to fully rise to the occasion. Director, choreographer, and all-around genius Susan Stroman does her best to thrill and dazzle, and several unique staging decisions (from an ingenious train to a three-sided merry-go-round of scenes) provide both spectacle and plot-points that drive the story (the climactic staging of the play features a spinning behind-the-scenes look at the play-within-the-musical), yet it lacks a cohesive arc. Part of this is due to the source material: at once a love letter and a Dear John kiss-off to Broadway, especially its critics. Ruminations of the value of art versus the value of a human being feel heavy-handed in a show that wants to delight with sheer showbiz pizzazz. Its musical reliance on a few tried-and-true standards also feels like a tepid retreading wanting for deeper resonance, something that connects more.

That said, praise must still be sung for that cast, those fine performers who carried it into the realm of something spectacular. It showcased the magic of artists at the height of their power, making the most of what they are given, and putting on a performance that made everyone in the audience a believer… even if it was the very last time.