If this was a Saturday night in my teen years, I would most likely have been at a smoky home in the south side of Amsterdam, at a table crowded with older women and a couple of female friends my age, playing a card game called dimes, adorned in some ridiculous wardrobe, and acting unlike almost every other teenage boy in America ~ and you would have seen me at my happiest. Also at that table would have been my friend Ann’s mother, Virginia ~ Ginny to everyone who knew her. She passed away this morning, and I’m writing this to honor and remember her. It’s all I can do in this dark time.

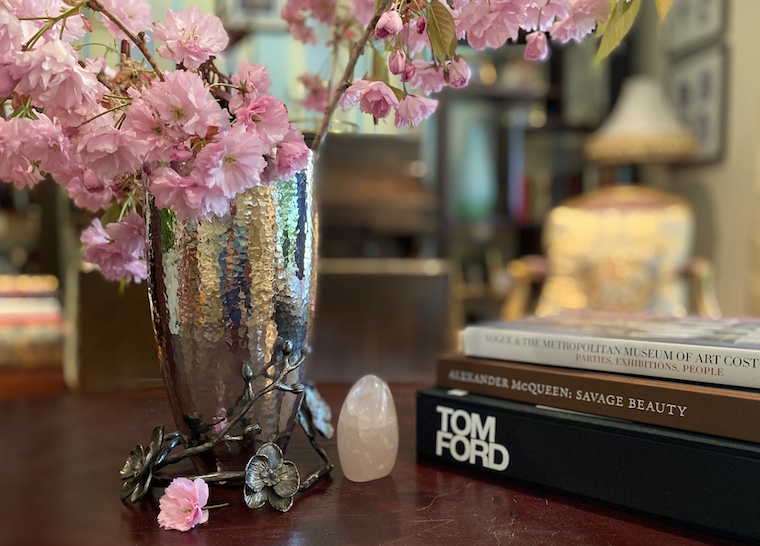

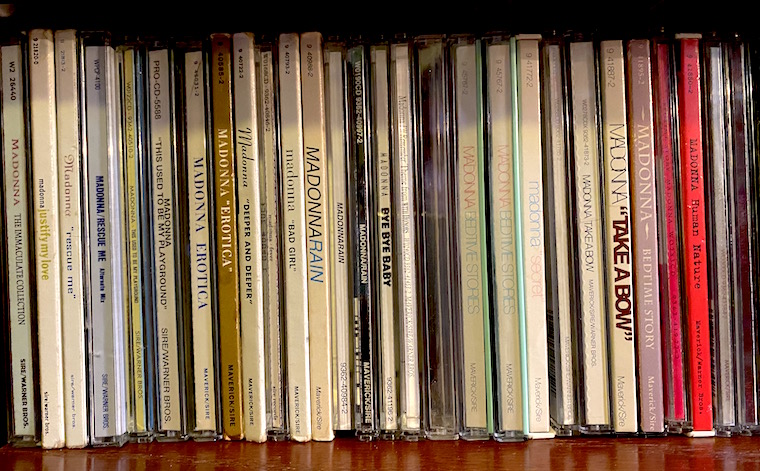

She is the woman who bought ‘Sex’ for me. The year was 1992 and I wasn’t eighteen yet and the stores wouldn’t sell it to anyone my age. But Ann’s mother drove us to the Rotterdam Mall where we picked up Madonna’s ‘Sex’ book and ‘Erotica’ album, imprinting an indelible memory of hilarity and fun in my life. In those days, I didn’t have much of a social life and my family situation was strained with the burgeoning confusion of a gay boy’s adolescence steeped in the strict Catholic upbringing of my parents.

My friend Ann was a bit of an outsider too, and when we found each other it came at just the right time. She welcomed me into her family ~ so different and so much more fun and looser than mine, a bit crazier too, but crazy is sometimes what a kid needs. At the heart of it was her mother, Ginny. She was no-nonsense, put up with little to no shit, and could be as gruff and tough as she was sweet and vulnerable. She adored and doted on Ann, and counted on her even as she was the youngest.

Every weekend, I hung out with Ann, and we would end up at a card game with her Mom and a few other women from the neighborhood. Ginny, Julie, Janice and Barb welcomed me to their card tables, which rotated every week at a different home. No matter what was happening in the rest of my life, those Saturday night car games became a grounding place of safety for me.

When things at home weren’t good, when I couldn’t find acceptance in my own house and from my own family, I turned to mother figures like Ann’s Mom. All those card-playing older ladies became surrogate mothers to me at a time when I didn’t know how to relate to my own family. On Saturday nights I would assemble at their kitchens, decked out in some insane ensemble, usually with a hat perched atop my head or some collection of rosaries around my neck. We carried ourselves like we were celebrities, and maybe in the south side of Amsterdam we were. I kept my head held too high to make much of whispers.

One night on a break from college I walked in wearing silk pajamas, a silk robe, and bandaged wrists. They asked about it only once, and it was enough. In their concern was the only lesson I needed.

We saw each through life and death like that. I grew up and left the warm smoky lair of those mother dragons. They sharpened my claws and toughened my scales. Ann’s Mom was an especially strong figure in that circle, fiery and passionate one moment, and immediately breaking down into laughter the next. I could have that effect on her, and my love for her daughter protected me, endearing myself to her. I called her Gin-Gin, and she rolled her eyes at me, half-exasperated by my silliness and half-enchanted by it. She held equal admiration and enthrallment from me. In the beginning, I would watch her as she lit up a cigarette and expertly doled out cards, her bracelets and rings dangling and sparkling and fascinating me in the light and the smoke. A couple years later she stopped smoking ~ simply and instantly stopped and never looked back, a study in strength and defiance.

Like Ann, she had a ferocious sense of humor. I did my best to make her laugh, which alternately annoyed and entertained her, and she was always game and up for any of my crazy requests. (See the ‘Sex’ story.) At every card game there would be a few moments where both of us ended up laughing so hard we could barely breathe, my stomach sore from the underutilized muscles that made us laugh, my face exhausted from seldom-seen smiles and all-too-rare glimpses of happiness.

Gradually my attendance at the card games dwindled. Ann and I went away to college, though we returned on certain weekends and holidays and summers and would reconnect and reconvene at someone’s house for a game of cards. And every time it was like nothing had changed, even if everything had. We moved out of Amsterdam and forged our own lives, and every now and then we would get together, but the ladies were growing old. We all were. Weddings were replaced by funerals, and one by one these women began to disappear. Ginny held on longer than most of them. She was always the strongest and most determined.

A while back I visited her at the nursing home. Ann had warned me she wasn’t always herself and would try to get me to take her out of there. It was a late summer day as I made my way along the Thruway, further west than Amsterdam by an exit. On the rural roads leading to the nursing home, stands of corn stretched to the sky, the ears fully formed and showing bits of their silky tassels like proud graduates. It was sunny and beautiful out ~ too beautiful for the sadness of seeing someone grow old, but there was beauty in that, I reminded myself as I walked into the building. I found her easily enough and she was in a wheelchair by her room. Unsure of whether she would recognize or remember me, I approached cautiously. It took only a moment, and then she knew me before I had to introduce myself. A few glints of mischievous determination returned to her eyes. We talked a bit as I crouched down to get closer to her. She leaned in and whispered conspiratorially, the way she sometimes did at those card games when she wanted to tell me a secret. “Al, you gotta get me out of here,” she said with a little smile.

“All right,” I said. “Let’s go to the dining room.” One of the nurses showed me where to go and I pushed Ginny around the corner and into a sun-filled room where a handful of other people sat at various places. Some waved and said hello. Ginny waved and said hi to a few, then beckoned for me to stop at our own little spot, whispering how this person was crazy, and that person was nice, and it was like nothing had changed. I remembered how she would drive me home after every card game: “Bye Al” she would say, adopting Ann’s nickname for me, then drive back over the bridge to the south side of Amsterdam, back to her own family.

She motioned for me to come closer. “Listen, I need to get out of here. Will you get me out of here?”

Ann had prepared me for this, thankfully, because if it had come up without me knowing it would come up, I’m not sure what I would have done. Part of me wanted to take her out and drive somewhere to talk and play cards and eat ham salad sandwiches and rewind the years and the toll they had taken on us. Instead, I told her that she had a nice place here, how much I liked it, how fancy it was to be taken care of, and how I would love such a set-up. She half-chuckled at the line of bullshit, but maybe she believed it. She only asked one more time to take her out of there, squeezing my hand as she did so, and I politely declined and told her Ann would be visiting in the next week, and she would want her to be there. By the time I had to leave, it felt like she had returned a bit to the woman I remembered. It was the last time I saw her, and I’m glad for that. Before driving away in the summer sun and heat, I paused in the parking lot, wanting to cry but not knowing why or how.

She is gone now, and my heart breaks for Ann, who has lost so much. On this beautiful sunny spring day, Ginny can join her husband, and her two children, Gina and Danny, and maybe there is solace in that.

Maybe.