Today marks thirty years to the day that my childhood friend Jeff killed himself. For about the first ten of those years I thought about him at least once a day. Not always in a sorrowful, all-encompassing way that stopped the day in its tracks – mostly just a quick blip of a memory, a reminder that I was here and he was not, and then I could move quickly on – but always at least once every single day, for at least ten years. That seems strange to me now, and I wondered if even his closest friends kept on doing that, whether they were as haunted as I was for so long, especially since I wasn’t even close to him in those last few years.

It had been a long while since that happened, and then this past week he came to mind as I was driving to Boston. Most of the trip was spent thinking of him in ways I hadn’t for years, going over every little interaction, recalling things I’d buried in my haste to get on with living. That’s when it dawned on me that this May would mark thirty years since he left.

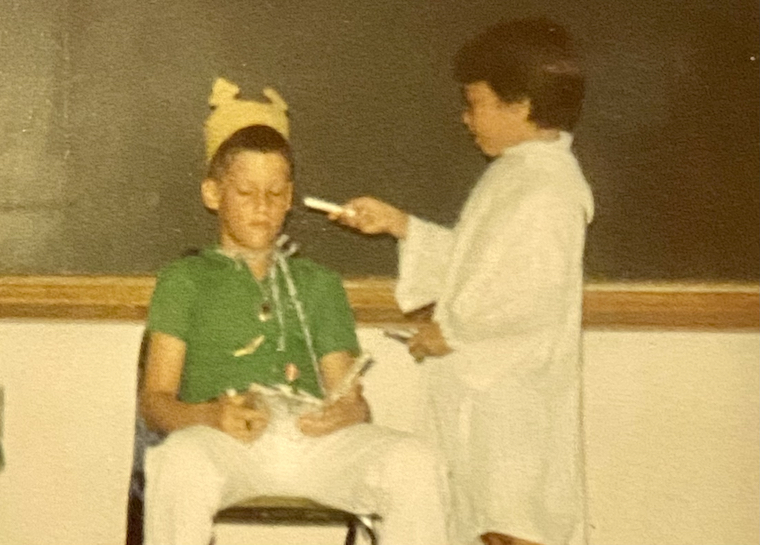

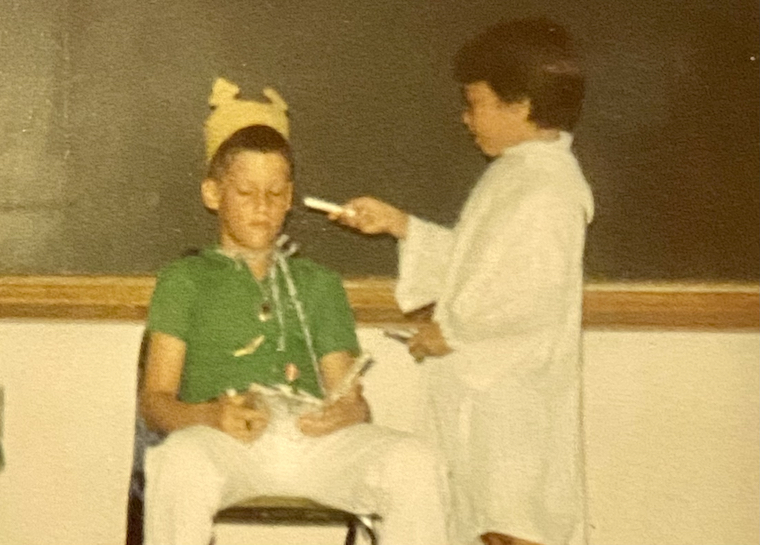

I remembered our second grade play, when we had a scene together in what would become a strange tradition: fate binding us together at the unlikeliest times, and in the unlikeliest ways. We were two kids that could not have been more outwardly different – he towered over me by at least a foot, generously outweighed me in muscle, and was handsome even at a young age in a way that I would never be.

He played a king, and I played his doctor, and that’s all I really remember about the play. It was only right that Jeff should be king – so tall and strong and physically imposing was he – and so well-liked by everyone. We were merely his court and admirers, yet despite his crown I sensed he never really felt it. He could have squashed me at every turn, but somehow I was the one who did the terrorizing. Jeff had all the physical power, but rarely did he use it – and it wasn’t because of some self-assured confidence in that power – his refusal to step up and take the place of leadership seemed to stem from uncertainty in other areas.

The same year we did that play, our teacher gave us blank folders that would visually indicate our progress with the addition of a sticker for every good day of schoolwork that we did. It began with stars, then branched out into holiday-themed stickers. As the folders on some of the smarter kids began to fill up, it became a competitive challenge to see who would have the most by the end of the year. (There were prizes in play.) At some point Jeff told his Mom that he wished he had as many stickers as I did, and my Mom relayed the information, perhaps sensing my own lack of faith in myself. Of course I promptly took that information and held it over him, simply because it was the only thing I thought I might be better at. It never dawned on me that he might envy someone else, and the idea that he was impressed by something I had done touched me. When I realized he was embarrassed that I knew that, I instantly wished I hadn’t said anything. The way I had sometimes made fun of him, in the way I made fun of everyone, suddenly felt wrong, but it wouldn’t stop me from doing it because I foolishly assumed he understood my sense of inferiority.

A litany of those misunderstandings would come to characterize our grade school friendship, always fraught with some underlying tension, always skittishly and intentionally cooled down whenever we might be warming to each other.

By sixth grade, and the end of our years at McNulty Elementary School, we felt like war buddies. We walked down center stage of the auditorium together rehearsing another play, some Greek drama where he was the lead, and I played two blessedly minor parts, the first of which was an old man. The two of us opened the show, and the only thing quelling my nerves was the fact that Jeff was by my side. Whether he understood it or not, and most likely he didn’t because I would have done everything in my power to pretend it wasn’t true, he was my protector – against everything that was about to happen to us. With Jeff next to me – and all his accompanying power and might and popularity – I might be ok. When my social anxiety roared, he was there as my comfort point, and he didn’t even know it.

I’ve never talked about those moments with anyone, and honestly I haven’t thought about them in decades. When he died in our junior year of high school, it was the horror and shock that overrode the quieter times we had. By then we had grown apart, and I barely remembered the friends we might have been to each other.

In so many ways, I didn’t grieve back then like I should have. It wasn’t in my power to do that – it was all I could do to survive on my own, to take the damn SATs the following day, to put my own suicidal thoughts aside. Somewhere, some part of me understood that if I started to grieve him then I might not make it out. If I had allowed myself to cry, I might not be able to stop. And so I shut down completely, and so impenetrably that I’m only now beginning to understand the toll it has taken for all these years. Maybe that’s why it took so long to push him out of my mind for a single day. When he died, I’d known him for far longer than I didn’t know him, and that sort of loss hadn’t happened up to that point. To lean into it, to feel that kind of profound sorrow, proved too much. Instead, I began a very slow process of grieving – the sort where he would be with me every day for the next decade, haunting my every step, doling out little pricks of pain instead of one drastic cut.

It was our last meeting that has stayed with me most stubbornly, and it came up again as I drove along to Boston. If I could just examine it one more time, put together the pieces in a way that would suddenly reveal a new key that would unlock the mystery and free the ghost, maybe that was how I could end it. Maybe that was the way to come to terms with it all these years later.

It was near the end of the school day. The hallway of Amsterdam High School had quickly cleared out and only a few stragglers remained. I was crouched down on the floor putting books away or grabbing notebooks for home, as moody as ever for no discernible reason. Sensing another person to my right, I looked up and saw Jeff standing there near his locker. Our last names had kept us together – ‘J’ following ‘I’ – at every alphabetical opportunity, and here we were near the end of our junior year. He was looking down at me, and though I had made some gains in height, even after I stood he was still looking down at me slightly. On his chest he wore a silver cross on a black cord. It was something I would have worn, and it seemed out of place on him. I remember noticing that first, and then noticing that he was staring at me. Unsure of whether he was about to make a disparaging comment or smirk and laugh at whatever I might have been wearing that day, I snarled an annoyed, “What?” in his direction. He didn’t smile or launch a counter-attack, he merely looked at me with eyes that suddenly seemed doleful and lost, and I was rendered completely silent from how uncharacteristic the reaction was. Jeff had never looked so empty, and I couldn’t reconcile the haunted boy before me with the invincible basketball jock that all the girls wanted to date and all the guys just wanted to be.

It was only a moment, and it passed quickly, no matter how much I slow it down in my mind, no matter how many times I replay it. He shook his head a little, because I still looked annoyed and was waiting for him to respond, and then he walked away. That’s where it had always ended for me – in a mystery, an untold secret forever locked by his death a few days later – and that’s where I always left it.

Only on this day, at the age of 46, I let myself feel it for the first time, and suddenly I was crying while careening along the Massachusetts Turnpike, letting out tears that had been waiting to fall for thirty years. As I went back to that moment in high school – our last moment together on this earth – I raged at myself, and I raged at Jeff, and I raged at a world that didn’t let a friendship between two very different boys survive to help us through that week. Why didn’t I just let down my defenses when I saw him that way? Why didn’t I just ask if he was ok? Why couldn’t he see beyond that one moment when it must have felt so hopeless to realize how much the rest of us all loved him?

When the tears slowed, I was left with a dull ache of regret, and something that I never realized before because I buried it too deeply in shame: I wish I had been a better friend to him.