Several weeks ago I saw a local production of ‘The Boys in the Band’ and left sorely unimpressed with it. I’d managed to avoid the movie version all my life based on the roundly negative perception that had been gleaned in the ensuing years of gay evolution, but I didn’t want to go in to the current revival wholly unprepared, so I watched a local troupe do the best that they could.

It felt so dated, so acerbic, so harsh – I didn’t recognize the joy I’ve mostly felt when surrounded by my gay friends. Yet was it the play that was problematic? Or was it my anger and issue with the fact that it was, at its time, an accurate reflection of how gay men lived and were perceived? Or was it my discomfort that some of those very same themes and issues still held true to this day? Whatever the reasons, I went into the current revival – staged fifty years after its landmark premiere – with these doubts hovering in my mind.

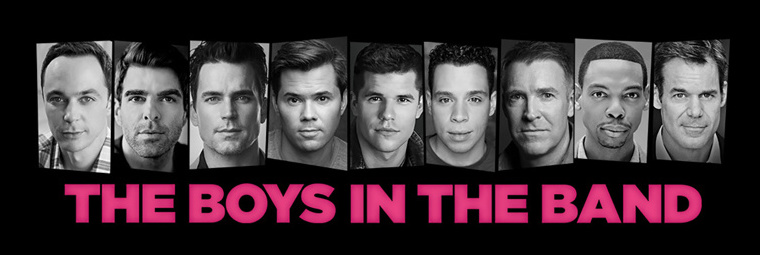

Back on Broadway with a thousand-watt cast and pedigreed director, ‘The Boys in the Band’ is one of the hottest tickets in town. The questions that bothered me on first viewing were still in effect, but director Joe Mantello (who lately has been averaging about two directorial pieces per season, and whose previous work includes ‘Love! Valour! Compassion!‘ and ‘Wicked‘) and that perfectly-assembled stellar cast managed to pull off a brilliant feat: bringing back a piece of the past, keeping it faithful to the original material and era, yet somehow making it completely of-the-moment and eerily relevant. (If anyone thinks that our fight was over when marriage equality became the law of the land, check out the vitriol on any number of social media sites. Hatred comes as much from the outside as it does from within.)

Brilliantly-lit and designed, the set is all about surface and reflection – mirrors and glass work to obscure and reveal. As the evening progresses, it gradually gets ravaged, and by the end it’s as messy as all the emotions that have been spilled. The main draw of this production is the cast, and at first I wondered whose star might shine brightest; the good news, and what makes this show work so well, is that they all do. Mantello has insured that each gets a little star turn, but it’s the ensemble work that propels these boys to a greater glory. Working together in finely-tuned nuance and dexterity, they seamlessly weave their own individual tales among the birthday proceedings at hand, flawlessly executing the cadence of the gay world as it exited the 60’s and charged into the 70’s. The sexual freedom on hand portends the arrival of AIDS in the 80’s, which makes this time capsule of gay history especially poignant in a way the original production could not have achieved.

Jim Parsons elicits the complexity and tightly-coiled danger of the evening’s host Michael, gradually coming undone as the night wears on, ending a brief bout of sobriety and giving in to his own demons. His is the rough, wounded heart around which the show delicately revolves. A former one-time paramour, Donald, endearingly played by Matt Bomer, is the first to arrive and set his mind at relative ease. Providing a sweeter foil to the perfectly prickly Parsons, Bomer provides both a calmer presence and some swoon-worthy eye candy (if you want to see him in briefs and briefly naked, it’s worth the price of admission).

Robin de Jesus sparkles and almost steals the show as Emory, deftly devouring the scenery in moments that run from the highest camp to the most lowly pathos, while somehow managing to steer clear of a grating stereotype. Michael Benjamin Washington brings a subdued elegance to his role as Bernard, even as he leaves in tears and regret. The catalyst that provides all the immediate drama is the arrival of Michael’s college friend Alan, the sole straight person in the story, whose overt posturing and derogatory comments belie past secrets operating on multiple levels. Brought to anguished life by Brian Hutchison, Alan may be the most conflicted of them all, a rather stunning reversal of the expected standard order. Birthday boy Harold appears half-way into the evening, but makes perhaps the biggest impression. Masterfully brought to life by a wickedly unrecognizable Zachary Quinto, his feathery, deliberately-cadenced delivery is as delicious as it is diabolical. Wit and sharpness have helped him survive, and all the vitriol that Michael throws at him falls away like so many broken arrows.

As mentioned, each character gets an indelible moment to show-off, and no one is one-note accent, which is quite an achievement. Even the Cowboy (Charlie Carver, in an almost-silent role) makes the most of his few words; his emoting, with the slightest switch in expression in a room of sharper wits, manages to convey innocence, exuberance and earnestness in a performance that is sweeter than it deserves to be.

Portraying a couple perpetually on the verge of a break-up or break-down, Andrew Rannells and Tuc Watkins inhabit Larry and Hank in realistically antagonistic fashion, yet despite the seeming precariousness of their relationship, they ultimately provide the evening’s singular moment of hope and sentiment. In a world that once openly hated us, and in some circumstances still does, the tortured yet honest way they navigate their lives is, in a warped way, one example of how gay people worked to forge their romantic relationships. That’s indicative of this play on a broader scale, and if we don’t see ourselves as readily in these characters, perhaps that’s the best sign of how far we’ve come. Taken as such, the work becomes a celebration. What might outwardly be seen as a sad little birthday party becomes a glorious revelry, thanks largely to the compelling performers who breathe life into a world that has, for better or worse, faded away.