The question caught me off-guard, not just in its meaning, but in its delivery. I’d just had dinner with my family, but instead of driving straight to my home, I stopped at my parents’ place to pick something up. I had made it into the house before my family arrived, so I was standing in the kitchen when my nephew bounded in and found me there. Usually, I would have just driven home and not been in my parents’ place at that time, so he was unaccustomed to seeing me there.

“What are you doing here?” he asked, half-wonderingly, half-accusingly.

“I… I… well, I live… I used to live here. This is still…” and then I tapered off because either he lost interest or I lost the words to explain. It was a simple question, a harmless and meaningless question from the mouth of a four-year-old, and yet it meant so much more.

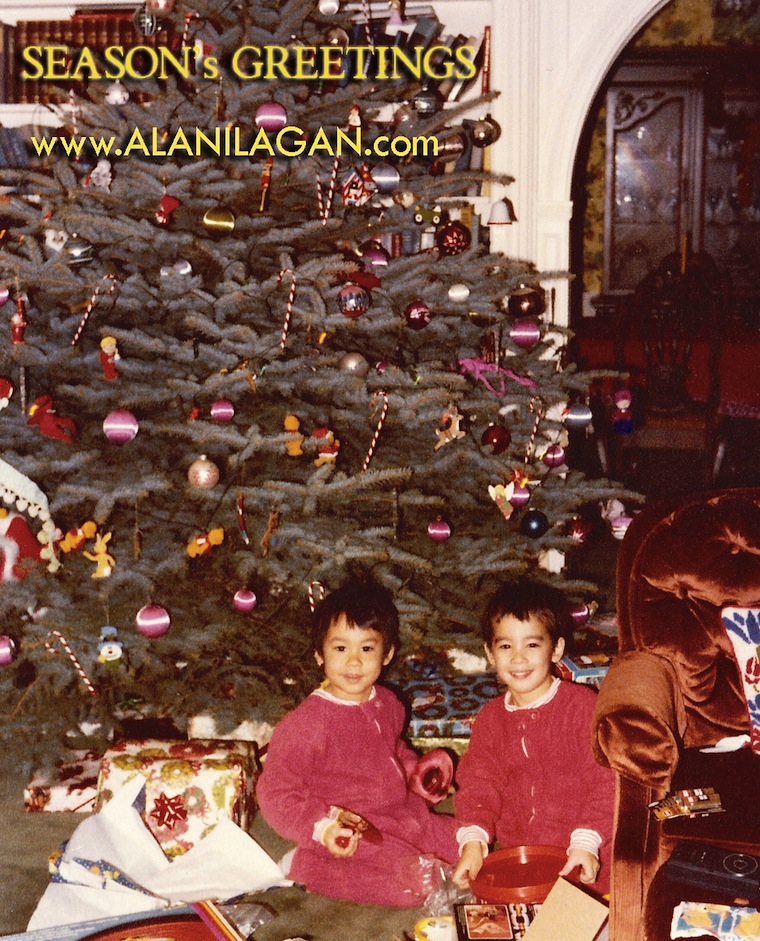

A few days later my Mom e-mailed me to tell me that they were going to set up a bunk bed in my childhood bedroom for the twins, trying as diplomatically as possible to explain that my room was going to be theirs. In truth, Andy had told me as much because she’d already told him. I’d braced myself for what it would make me feel, trying to work through whatever anguish or unreasonable sense of possession I felt over the room where I’d grown up (and in which, on the occasional night of difficulty, I still found solace and safety) before the actual news was delivered. Of course, you can’t practice for pain, especially when it’s delivered by your own family.

I realize that was foolish of me. Not just to feel so hurt by the action, but to even think I held any ownership or claim to a childhood bedroom. My mother explained that there was more history to that room than my time in it, and that, in her words, “It is the season for nostalgia but these are also times for passing the torch, so to speak, for new traditions and new directions.”

I felt foolish for feeling so hurt. She was right. My brother lives there. His children live there. My parents live there. The only family member who doesn’t live there is me. It’s only fitting that I should not have a room or place of my own in that house. In truth, I haven’t felt part of that home in years, and it’s as much my fault as anyone else’s.

Like my mother, I remember every incarnation that room went through as I grew up. I remember when I was old enough to ask for a change in the wall-paper – it had been a striped background with blue soldiers ever since I could remember – and in a last-ditch effort to win over my father I chose a new pattern of horses with a border of a horse race – hoping that his love of OTB and betting on horses would somehow translate to a new love of his first-born son. Following his lackluster reception, I think I gave up on trying to make him proud, or even trying to get him to like me in such blatant, pandering ways. (In his defense, I don’t think I was a very likable child.)

But before that, my parents had kissed me goodnight there. In the days before I grew into whatever it was that made people draw back, into whatever off-putting version of myself that kept love at bay, that made people hesitate and pause, I’d been loved – unconditionally, unquestionably, undeniably loved. That sort of love comes, if we’re lucky, once or twice in our lives – and, if we’re very lucky, it starts in childhood. That was what I remember most about that room – not the soldiers or the horses or the pattern of the air-duct grate – it was the love.

That’s why it was hard to let go. Part of me thought there was still some remnant of the boy that I was still inside me, still worthy of that kind of unconditional love. Part of me thought if I held on to that room, there would still be a chance to unlock that love again. But I was wrong.

It’s time for two other children to get that love. I hope they can hang onto it longer than I could.