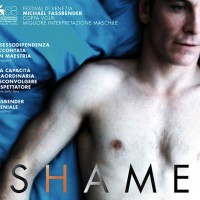

It is a secret I’ve kept for almost two decades.

I’ve kept it a secret because it was the ultimate sign of weakness, and it’s so far removed from who I am today that a different sort of shame began to attach itself – the shame of having felt shame in the first place. That’s the insidious nature of shame – it builds upon itself, wrecking and destroying as it goes, eating up energy and taking up more space as it feeds upon itself.

It’s the real reason I didn’t attend my high school graduation.

In June of 1993, I was set to graduate from high school. While all my classmates were being fitted for graduation gowns and rehearsing our final ceremony together, I stayed away and kept to myself. As I missed the last rehearsal, I had sealed my fate: while graduating near the top of my class, I was not going to attend the graduation ceremony.

I’m sure I came up with some lame excuse, some self-aggrandizing notion of not believing in such pomp and circumstance, some rebellious stance of going against the masses – and in some small way each of them may have been true. Contrary to popular belief, I’ve never been comfortable with big accolades, especially those accompanied by ceremony and public displays of congratulation.

Yet that wasn’t the real reason I didn’t go.

Here, almost twenty years later, I am ready to reveal it.

It wasn’t pride, or that I thought I was better than anyone else.

It wasn’t a statement of any kind.

It was the simplest of reasons for why we do so many things: it was shame. I was afraid someone would yell out ‘fag’ as I walked across the stage to pick up my diploma.

That was it. That was all. That was everything.

It was and it wasn’t such a far-fetched notion, and the only reason it became such a fear is that it had happened a couple of times on a lesser scale. In band, whenever I had to play a solo in front of the class, one or two guys would shout/cough as they said, ‘Fag’ almost-but-not-quite under their breath. We all heard it. If you’ve never been called something like that, you can never know the instant shame that you feel when it happens. It’s visceral – it burns the face, it catches the heart, it takes your breath away. It’s a feeling of panic, of being found out, of being accused and guilty all at once. It’s something no teenager or child should ever feel – not for that, not for something so innocent.

And so I created a list of excuses and reasons for not going. I knew it would be a disappointment to my parents, who would not get to see their first-born child pick up his diploma, but I couldn’t face the possibility of being called out. I wasn’t that strong. I wasn’t that resilient. And I wasn’t ready to face the fact that it was true.

There had been no one to tell me that it was all right.

There had been no one who lived openly as a gay person in high school then to show me it could be done.

Instead, there had been a boy I didn’t even know, over a foot taller than me, stronger and full of fury, who came up to my lunch table, slapped me across the face, called me a ‘fag’ and asked what I was going to do about it. I hadn’t even known his name, and had never had a single exchange or interaction with him. That’s one of the most fearsome parts of hatred and ignorance. It comes out of nowhere, from people who don’t even know you, without reason or sense, and it instills a constant suspicion of the world, a mistrust of fellow human beings, a sorrowful disappointment in humanity.

There would not be a chance for anything like that to happen in public again. I sat at home while the rest of my class graduated. I never turned a tassel over (how many ensuing tassels would I wear over the years to make up for it?), I never shook hands with a smiling figurehead, I never tossed a silly black cap in the air. There was no official end to my high school years. I departed in the dark of night, with no good-bye, no bittersweet ritual of ending, no proper way to move on. I gave up a rite of passage, and to this day it’s impossible to calculate the cost of that. Yet as much as I want to regret all of it, I can’t.

While part of me cowered, part of me grew crafty enough to create a way around it, a path that led people to believe I was removing myself from the situation due to loftier goals, and a holier-than-thou opinion of myself. If that’s what it took to set up the smoke-screen, that’s what I would do. It would be a safety mechanism where I would assume the posture of rising above everything, as if I didn’t care, as if it was all nothing to me.

Only now can I admit how much I did care, and how much I hurt. The one thing I thought was a sign of weakness to say is what I am now able to publicly put out there: yes, it hurt me. Yes, it embarrassed me. Yes, as a seventeen-year-old kid in high school, it scared me. And because of all of that, it silenced me. I banished myself from my own high school graduation. I was defeated. The kid who slapped me and called me a fag walked across the stage and got his diploma, while I sat home alone on that sunny day in June.

It was a secret created in shame, and kept as such because of shame. A secret that festered and grew inside my heart – there and only there, in the worst possible place to keep it – and my efforts at subterfuge and disguise built a strength and fortitude I knew I needed but never thought I’d have. Somehow, I did it.

Through sheer will-power and a belief in myself founded utterly on delusions and illusions, I created the persona of the egocentric embodiment of aloofness, where nothing or no one could ever touch me. No one could slap me or call me a fag – and if they did it would have absolutely no effect on me ~ so far above and beyond did I so desperately wish to appear, and it worked.

It brought me to where I am this very day, and has served me well. Eventually we are all just the image we have presented to the world, even when we are not. Still, it was built on shame and fear, and while I want to think I’ve turned it into something good, it’s always bothered me, and I don’t want it to be a secret anymore.

Let this be my small way of taking back a bit of what I allowed others to take away from me those many years ago. Let it also be a sign of hope that it’s never too late to fight – never too late to acknowledge injustice and pain – never too late to try to make it better for someone who might be going through the same fear and trepidation.

My high school and college years could have been so different, so much happier, so much more of what they should have been, if I’d only felt comfortable, if I’d only felt safe. I think that’s the greatest regret of my childhood: that I didn’t feel safer. No child should have to feel the terror that most gay kids feel at one point or another. In my college years, I pushed people away, not so much overtly as unconsciously. How could they get closer to someone they could never know? And how could I let them know me when I was so afraid they wouldn’t like me because I was gay?

People can usually tell, maybe not specifically why, but they can sense when you’re not being genuine or honest, either with them or with yourself. It lends an insurmountable distance, a barrier that keeps others at bay. It may seem safer that way, but it’s lonelier too, and much more debilitating than any pain that might result from being true to yourself.

It’s a little late in the game, and a little emptier and less brave now that I’m married and don’t have to fear high school anymore, but for what it may be worth to someone else, I offer the secret on why I missed my high school graduation.

I know it’s not easy. I know that not everyone has had the advantages and privileges I’ve been afforded (and even with them, look at how little I’ve actually been able to accomplish). But I also know that things are changing.

Part of me will always be angry for what I allowed them to take from me, those two decades ago, but it’s time to move on. It’s time to let it go. Twenty years is long enough.